Lucius Walker Jr.

On Friday, I attended the service for Lucius Walker, Jr. at the Convent Avenue Baptist Church. The church was packed with family, friends and colleagues. Two choirs sang out passionately. To me the most moving moment was when the recent graduates from the Cuban Medical School stood up. Latino and African American young people have been trained in Cuba to become doctors: 47 have graduated and there are now 145 US youth currently at the school. I had seen them sitting together and thought it might be a third choir-- they were all dressed in white. As the service went on and they didn't sing, I began to wonder who they were. Then someone at the podium asked "the doctors to stand." There were few dry eyes in the audience, as we all rose with the doctors to give them a standing ovation. Many of them have recently returned from Haiti, where they have been administering to those wounded in the terrible earthquake.

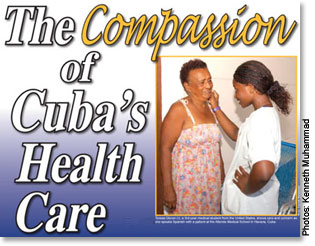

Executive Director of Pastors for Peace Rev. Lucius Walker Jr. (c) stands with (l-r) Melissa Barber, Toussaint Reynolds, Kenya Bingham, Jose Deleon, Cedric Edwards, Teresa Glover and Evelyn Erickson, who were part of the initial student population that launched the program at the Allende Medical School.

Article from Finalcall.com :

More doctors equal better health

HAVANA (FinalCall.com) - While major media reports the war of words between America and Cuba over President George Bush’s new economic sanctions, very little, if anything, is being said about President Fidel Castro’s offer of 500 yearly medical school scholarships to solve the health crisis in the Black community.

“We are prepared to grant a number of scholarships to poor youth who cannot afford to pay the $200,000 it costs to get a medical degree in the United States,” said President Castro in 2001 when he announced the offer while speaking in New York.

A major problem in the health of the Black community is the lack of Black doctors servicing poor and needy Black patients. With rising costs in medical schools and limited openings for Black students, the problem appears only to worsen.

The Latin American School of Medical Sciences (LASMS) here stands ready to educate a minimum of 500 doctors each year—for free. The only requirement is that, after they graduate, they must come back to the United States and practice medicine among the poor.

The program is organized by the Inter-religious Foundation for Community Organizing (IFCO)/Pastors for Peace which is under the direction of founder Reverend Lucius Walker. On May 24-29,

Rev. Walker headed a U.S. delegation to tour the medical school facilities. The first stop was the Salvadore Allende Medical School, which trains third through sixth year medical students.

“Yours is a noble profession. You must be missionaries and ministers committed to the full development of the people you serve. Go into the world and build a better world, a healthier world. You may become leaders in your community. Take dignity and respect for the poor and commitment to build a new world with you as you go out to become doctors,” Rev. Walker said to the students.

After he spoke, Teresa Glover, a third year student from New York City, came looking for him with open arms.

“He’s the reason I’m here,” she told The Final Call. Ms. Glover graduated from the State University of New York in 1998 with a degree in biology, after which she got a job and worked for three years. In 2001, she heard about the medical school program and called IFCO.

“I love the school. I really want to be a doctor and couldn’t have done it any other way. I started working with patients right away. Now that I’m in my third year, there are more hands on interactions with the patients.”

Her biggest adjustment is being away from her family and the inability to call home regularly because of the economic sanctions.

“I got married after my first year and my husband, James, is my biggest supporter. We’re determined to make it work,” she shared.

Cedric Edwards is from New Orleans and has a combined molecular biology and biochemistry degree from Middleburg College. He is in his fifth year and will be the first U.S. graduate next year.

“I’m very excited about graduating, but I’m also concerned about the problems between the U.S. and Cuba. I really want to practice medicine in the United States and help poor people get better health care,” he told The Final Call.

Melissa Barber always wanted to be a doctor. Her degree from Ursinus Collge is in chemistry and Spanish.

“I went to a boarding high school, so I’ve always lived away from home. This is an exciting program. They’re teaching me to be a great doctor. I’ve learned to integrate my patient care with what I learned in my first two years,” she told The Final Call.

An export of great importWhat Cuba is doing for the students from the U.S. is nothing new. This country is world renowned for educating doctors and exporting them where they are needed the most. Currently, there are 9,000 students from 24 different countries.

Cuba has offered the most student slots to the United States. Other countries have 3,000 students competing for the 50 slots that are offered. Cuba considers this work her humble effort to help all countries within their possibilities.

Since an overwhelming number of students were coming from Africa, Cuba is planning to open a medical school in Africa to serve all of the students who want to be doctors. This work of sending health professionals around the world has led Nation of Islam Minister of Health and Human Services Abdul Alim Muhammad to see Cuba as “the most compassionate country on earth.”

“What does Cuba get for sending doctors around the world? They get nothing. They really care about people. They really believe that people deserve and have a right to health care. They believe people deserve life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” he toldThe Final Call.

He recalled his first visit to Cuba in 1995. “They had 50,000 doctors for their 10 million people. Now, they have 70-80,000 doctors for 12 million people. They don’t need any more doctors. They have a doctor in every community, school and factory. They have the best doctor-patient ratio in the world, with one doctor for every 200 people,” he pointed out.

The ratio, in fact, is really better than that. Cuba boasts one doctor for every 165 people, according to the Cuban officials. The ratio in the United States is far worse.

“According to the National Medical Association, there are only 23,000 Black doctors in practice to serve 40 million Black people. How many patients is that per doctor? It’s one doctor for every 2,000 patients. That’s Third World health standards. We can’t elevate the health conditions of our people with that ratio,” Dr. Muhammad charged.

“For Whites, the ratio is one doctor for every 300 people. Whites have six times greater access to a health professional than Blacks,” he continued. “There are whole areas around the country where there are no Black doctors.”

Most doctors agree that people tend to get medical care from people who look like them and are more likely to relate to their own experiences.

Dr. Muhammad said, “We don’t have the manpower to do what needs to be done to improve our health. We need six or seven times as many doctors as we have now. How will we get them? This speaks to the greatness of what Cuba is doing.”

Getting into medical schoolIn the United States, there are only two predominantly Black medical schools, Howard and Meharry Universities. Many of the 80 students attending medical school in Cuba applied to medical school in their homeland, but weren’t accepted.

Sarpoma Sefa-Boakye is from southern California and is starting a student chapter of the National Medical Association. “They asked us why we didn’t apply to Howard or Meharry. I told them that we did, but we didn’t get accepted.”

In Cuba, there are seats ready and waiting for qualified students to apply. It doesn’t cost an arm or a leg either.

“I love it here,” said Nicole Murray from New Jersey. “The teachers are very concerned about you. In the U.S., you’re just a number and you’re expected to fail. If you miss a class, they come after you. [In Cuba,] the teachers look for you and ask you where you were and what’s going on,” she told The Final Call.

“The teachers are very strict,” added Jessica Barreto, who is from New Mexico. “The teachers really want you to be successful.”

For Desta Muhammad, a first year medical student from Los Angeles, the goal of becoming a doctor is what keeps her motivated. Like all of the other students, she misses home, going to Muhammad’s Mosque No. 27 and eating her regular food. In exchange for that sacrifice, she has learned Spanish, made numerous friends and is getting a free medical education.

“I want to be a doctor and this was the only way I was going to be able to do it. I love the program and encourage others to get involved,” she said.

The program consists of a six-month pre-med study which is designed to bring all students to a comparable proficiency level to begin their studies. Many from Latin American countries begin this process straight out of high school at the age of 16.

U.S. students tend to complete more schooling, which bears witness to the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan’s comments on the “dumbing down” of American education. Some can come straight from high school, but most attend at least two years of college first.

At the LASMS, pre-med includes courses in chemistry, biology, math and physics, an introduction to health sciences, history of the Americas, and a 12-week intensive Spanish language program for those who need it. Some students are able to opt out of pre-med with a placement test in the sciences and Spanish.

The program is based on intensive advising and tutoring designed to help every student succeed. Students must pass competency exams at appropriate points in their course of study.

A six-year medical school program follows, beginning every September, divided into 12 semesters. Students study at the LASMS campus for the first two years, and then go to another of Cuba’s 21 medical schools to complete their studies.

The Cuban medical school combines theory and practice and is oriented towards primary care, community medicine and hands-on internships.(For more information on the Latin American School of Medical Sciences, call the Inter-religious Foundation for Community Organizing(IFCO)/Pastors for Peace at (212) 926-5757 or visit www.ifconews.org.)

This is an obituary printed in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinal:

Long before Lucius Walker Jr. made international headlines - including for humanitarian aid to Cuba and when shot by U.S.-backed contra forces in Nicaragua - he was a minister and civil-rights activist in Milwaukee.

Walker arrived in Milwaukee in the late 1950s while still a theology student, first serving as a youth director for the Milwaukee Christian Center on the south side. Before he was even ordained, he was called to serve by Hulburt Baptist Church, an all-white congregation, also on the south side. He went on to serve as the founding director of Northcott Neighborhood House.

"Lucius was the first African-American professional we know of who was assigned to work on the then-segregated south side of Milwaukee," said activist Art Heitzer, involved with the Wisconsin Coalition to Normalize Relations with Cuba.

Walker was found dead Wednesday at his home in Demarest, N.J., likely after suffering a heart attack in his sleep. He was 80.

He was born in Roselle, N.J., earning his master of divinity degree from Andover Newton Theological School. While in Milwaukee, he earned a master's degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

In his calm, steadfast way, Walker refused to walk away when he witnessed discrimination. When he took a group of boys to a local roller rink in the 1950s - and the white teens were allowed to enter but he wasn't - he filed a civil rights complaint.

When Walker witnessed an off-duty officer making an arrest in 1967 - and the situation became heated - he refused to move along as ordered. Instead, he was among those arrested and fought the charges.

Hundreds of local priests, ministers and nuns packed the courtroom in his support. His character witnesses included former Milwaukee Mayor Frank Zeidler and E. Michael McCann, then an assistant district attorney. Walker later won on appeal.

In 1967, he also accepted a new position in New York. Walker was named founding director of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization, an ecumenical group that works for peace and social justice.

"He was a gentle storm," said Thomas E. Smith, a Pittsburgh minister and board chairman of IFCO.

"He went about in his quiet methodical way, not raising his voice but making his point," Smith said. "He fought calmly and courageously. He deplored violence, and he always thought there was a peaceful way to deal with things."

In 1988, Walker was leading a humanitarian mission in Nicaragua when their Mission of Peace passenger boat was fired on by contra rebels. Two people were killed. Walker was one of dozens of people wounded in the attack.

"Shots were whizzing over our heads," he told the Milwaukee Sentinel. "I saw women and children hit by bullets. I think the bullet that went through my rear end also struck the shoulder of a woman standing near me. . . . Blood was all over the place . . . people were screaming and bullets were ricocheting every which way."

His first thought after the attack was that "this is occurring because of . . . Reagan. He's sending arms over to these guys (the contras) and training them. I realized I was being attacked and facing death at the hands of my own government."

The attack inspired Walker to found Pastors for Peace as an IFCO project. The group continues to provide humanitarian aid to Central America and even assisted in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

In 1992, Walker led the first of 21 "Friendshipment" caravans of medical supplies and other humanitarian aid to Cuba. He refused to seek official permission, instead sending aid through other countries, including Canada and Mexico.

When humanitarian aid was blocked, Walker resorted to long hunger strikes until the goods moved again.

Walker was mourned in Cuba media this week.

"Cubans, in gratitude, have to say that we don't want to think of a world without Lucius Walker," wrote the Communist Party daily Granma.

"He's one of the most respected American people, if not the most respected, in Cuba," Heitzer said.

He led his last mission to Cuba in July, again meeting with former President Fidel Castro. Walker still served as pastor of Salvation Baptist Church of New York.

Walker believed that for many in both the U.S. and poorer countries, things were not better.

"Let us not buy into the notion that the civil-rights goal has been achieved," Walker said in 1993. "It has not. We should not think that because we have a holiday for Martin Luther King, we have made it. That is a token."

Executive Director of Pastors for Peace Rev. Lucius Walker Jr. (c) stands with (l-r) Melissa Barber, Toussaint Reynolds, Kenya Bingham, Jose Deleon, Cedric Edwards, Teresa Glover and Evelyn Erickson, who were part of the initial student population that launched the program at the Allende Medical School.

Article from Finalcall.com :

More doctors equal better health

|

| Teresa Glover (r), a 3rd year medical student from the United States, shows care and concern as she speaks Spanish with a patient at the Allende Medical School in Havana, Cuba. |

“We are prepared to grant a number of scholarships to poor youth who cannot afford to pay the $200,000 it costs to get a medical degree in the United States,” said President Castro in 2001 when he announced the offer while speaking in New York.

A major problem in the health of the Black community is the lack of Black doctors servicing poor and needy Black patients. With rising costs in medical schools and limited openings for Black students, the problem appears only to worsen.

The Latin American School of Medical Sciences (LASMS) here stands ready to educate a minimum of 500 doctors each year—for free. The only requirement is that, after they graduate, they must come back to the United States and practice medicine among the poor.

The program is organized by the Inter-religious Foundation for Community Organizing (IFCO)/Pastors for Peace which is under the direction of founder Reverend Lucius Walker. On May 24-29,

Rev. Walker headed a U.S. delegation to tour the medical school facilities. The first stop was the Salvadore Allende Medical School, which trains third through sixth year medical students.

“Yours is a noble profession. You must be missionaries and ministers committed to the full development of the people you serve. Go into the world and build a better world, a healthier world. You may become leaders in your community. Take dignity and respect for the poor and commitment to build a new world with you as you go out to become doctors,” Rev. Walker said to the students.

After he spoke, Teresa Glover, a third year student from New York City, came looking for him with open arms.

“He’s the reason I’m here,” she told The Final Call. Ms. Glover graduated from the State University of New York in 1998 with a degree in biology, after which she got a job and worked for three years. In 2001, she heard about the medical school program and called IFCO.

“I love the school. I really want to be a doctor and couldn’t have done it any other way. I started working with patients right away. Now that I’m in my third year, there are more hands on interactions with the patients.”

Her biggest adjustment is being away from her family and the inability to call home regularly because of the economic sanctions.

“I got married after my first year and my husband, James, is my biggest supporter. We’re determined to make it work,” she shared.

Cedric Edwards is from New Orleans and has a combined molecular biology and biochemistry degree from Middleburg College. He is in his fifth year and will be the first U.S. graduate next year.

“I’m very excited about graduating, but I’m also concerned about the problems between the U.S. and Cuba. I really want to practice medicine in the United States and help poor people get better health care,” he told The Final Call.

Melissa Barber always wanted to be a doctor. Her degree from Ursinus Collge is in chemistry and Spanish.

“I went to a boarding high school, so I’ve always lived away from home. This is an exciting program. They’re teaching me to be a great doctor. I’ve learned to integrate my patient care with what I learned in my first two years,” she told The Final Call.

An export of great importWhat Cuba is doing for the students from the U.S. is nothing new. This country is world renowned for educating doctors and exporting them where they are needed the most. Currently, there are 9,000 students from 24 different countries.

Cuba has offered the most student slots to the United States. Other countries have 3,000 students competing for the 50 slots that are offered. Cuba considers this work her humble effort to help all countries within their possibilities.

Since an overwhelming number of students were coming from Africa, Cuba is planning to open a medical school in Africa to serve all of the students who want to be doctors. This work of sending health professionals around the world has led Nation of Islam Minister of Health and Human Services Abdul Alim Muhammad to see Cuba as “the most compassionate country on earth.”

“What does Cuba get for sending doctors around the world? They get nothing. They really care about people. They really believe that people deserve and have a right to health care. They believe people deserve life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” he toldThe Final Call.

He recalled his first visit to Cuba in 1995. “They had 50,000 doctors for their 10 million people. Now, they have 70-80,000 doctors for 12 million people. They don’t need any more doctors. They have a doctor in every community, school and factory. They have the best doctor-patient ratio in the world, with one doctor for every 200 people,” he pointed out.

The ratio, in fact, is really better than that. Cuba boasts one doctor for every 165 people, according to the Cuban officials. The ratio in the United States is far worse.

“According to the National Medical Association, there are only 23,000 Black doctors in practice to serve 40 million Black people. How many patients is that per doctor? It’s one doctor for every 2,000 patients. That’s Third World health standards. We can’t elevate the health conditions of our people with that ratio,” Dr. Muhammad charged.

“For Whites, the ratio is one doctor for every 300 people. Whites have six times greater access to a health professional than Blacks,” he continued. “There are whole areas around the country where there are no Black doctors.”

Most doctors agree that people tend to get medical care from people who look like them and are more likely to relate to their own experiences.

Dr. Muhammad said, “We don’t have the manpower to do what needs to be done to improve our health. We need six or seven times as many doctors as we have now. How will we get them? This speaks to the greatness of what Cuba is doing.”

Getting into medical schoolIn the United States, there are only two predominantly Black medical schools, Howard and Meharry Universities. Many of the 80 students attending medical school in Cuba applied to medical school in their homeland, but weren’t accepted.

Sarpoma Sefa-Boakye is from southern California and is starting a student chapter of the National Medical Association. “They asked us why we didn’t apply to Howard or Meharry. I told them that we did, but we didn’t get accepted.”

In Cuba, there are seats ready and waiting for qualified students to apply. It doesn’t cost an arm or a leg either.

“I love it here,” said Nicole Murray from New Jersey. “The teachers are very concerned about you. In the U.S., you’re just a number and you’re expected to fail. If you miss a class, they come after you. [In Cuba,] the teachers look for you and ask you where you were and what’s going on,” she told The Final Call.

“The teachers are very strict,” added Jessica Barreto, who is from New Mexico. “The teachers really want you to be successful.”

For Desta Muhammad, a first year medical student from Los Angeles, the goal of becoming a doctor is what keeps her motivated. Like all of the other students, she misses home, going to Muhammad’s Mosque No. 27 and eating her regular food. In exchange for that sacrifice, she has learned Spanish, made numerous friends and is getting a free medical education.

“I want to be a doctor and this was the only way I was going to be able to do it. I love the program and encourage others to get involved,” she said.

The program consists of a six-month pre-med study which is designed to bring all students to a comparable proficiency level to begin their studies. Many from Latin American countries begin this process straight out of high school at the age of 16.

U.S. students tend to complete more schooling, which bears witness to the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan’s comments on the “dumbing down” of American education. Some can come straight from high school, but most attend at least two years of college first.

At the LASMS, pre-med includes courses in chemistry, biology, math and physics, an introduction to health sciences, history of the Americas, and a 12-week intensive Spanish language program for those who need it. Some students are able to opt out of pre-med with a placement test in the sciences and Spanish.

The program is based on intensive advising and tutoring designed to help every student succeed. Students must pass competency exams at appropriate points in their course of study.

A six-year medical school program follows, beginning every September, divided into 12 semesters. Students study at the LASMS campus for the first two years, and then go to another of Cuba’s 21 medical schools to complete their studies.

The Cuban medical school combines theory and practice and is oriented towards primary care, community medicine and hands-on internships.(For more information on the Latin American School of Medical Sciences, call the Inter-religious Foundation for Community Organizing(IFCO)/Pastors for Peace at (212) 926-5757 or visit www.ifconews.org.)

This is an obituary printed in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinal:

Long before Lucius Walker Jr. made international headlines - including for humanitarian aid to Cuba and when shot by U.S.-backed contra forces in Nicaragua - he was a minister and civil-rights activist in Milwaukee.

Walker arrived in Milwaukee in the late 1950s while still a theology student, first serving as a youth director for the Milwaukee Christian Center on the south side. Before he was even ordained, he was called to serve by Hulburt Baptist Church, an all-white congregation, also on the south side. He went on to serve as the founding director of Northcott Neighborhood House.

"Lucius was the first African-American professional we know of who was assigned to work on the then-segregated south side of Milwaukee," said activist Art Heitzer, involved with the Wisconsin Coalition to Normalize Relations with Cuba.

Walker was found dead Wednesday at his home in Demarest, N.J., likely after suffering a heart attack in his sleep. He was 80.

He was born in Roselle, N.J., earning his master of divinity degree from Andover Newton Theological School. While in Milwaukee, he earned a master's degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

In his calm, steadfast way, Walker refused to walk away when he witnessed discrimination. When he took a group of boys to a local roller rink in the 1950s - and the white teens were allowed to enter but he wasn't - he filed a civil rights complaint.

When Walker witnessed an off-duty officer making an arrest in 1967 - and the situation became heated - he refused to move along as ordered. Instead, he was among those arrested and fought the charges.

Hundreds of local priests, ministers and nuns packed the courtroom in his support. His character witnesses included former Milwaukee Mayor Frank Zeidler and E. Michael McCann, then an assistant district attorney. Walker later won on appeal.

In 1967, he also accepted a new position in New York. Walker was named founding director of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization, an ecumenical group that works for peace and social justice.

"He was a gentle storm," said Thomas E. Smith, a Pittsburgh minister and board chairman of IFCO.

"He went about in his quiet methodical way, not raising his voice but making his point," Smith said. "He fought calmly and courageously. He deplored violence, and he always thought there was a peaceful way to deal with things."

In 1988, Walker was leading a humanitarian mission in Nicaragua when their Mission of Peace passenger boat was fired on by contra rebels. Two people were killed. Walker was one of dozens of people wounded in the attack.

"Shots were whizzing over our heads," he told the Milwaukee Sentinel. "I saw women and children hit by bullets. I think the bullet that went through my rear end also struck the shoulder of a woman standing near me. . . . Blood was all over the place . . . people were screaming and bullets were ricocheting every which way."

His first thought after the attack was that "this is occurring because of . . . Reagan. He's sending arms over to these guys (the contras) and training them. I realized I was being attacked and facing death at the hands of my own government."

The attack inspired Walker to found Pastors for Peace as an IFCO project. The group continues to provide humanitarian aid to Central America and even assisted in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

In 1992, Walker led the first of 21 "Friendshipment" caravans of medical supplies and other humanitarian aid to Cuba. He refused to seek official permission, instead sending aid through other countries, including Canada and Mexico.

When humanitarian aid was blocked, Walker resorted to long hunger strikes until the goods moved again.

Walker was mourned in Cuba media this week.

"Cubans, in gratitude, have to say that we don't want to think of a world without Lucius Walker," wrote the Communist Party daily Granma.

"He's one of the most respected American people, if not the most respected, in Cuba," Heitzer said.

He led his last mission to Cuba in July, again meeting with former President Fidel Castro. Walker still served as pastor of Salvation Baptist Church of New York.

Walker believed that for many in both the U.S. and poorer countries, things were not better.

"Let us not buy into the notion that the civil-rights goal has been achieved," Walker said in 1993. "It has not. We should not think that because we have a holiday for Martin Luther King, we have made it. That is a token."

Labels: Convent Avenue Baptist Church, Cuba, IFCO, Interfaith Pastors for Peace, Lucius Walker, Medical School

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home